Maximum Representation: A call for inclusive data reporting

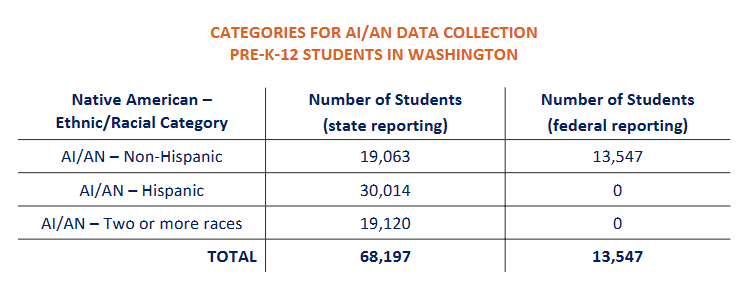

Last year, Washington STEM joined a new conversation around data: one that would help find more than 50,000 Washington students being undercounted in federal records and state reports. More specifically, we’re talking about students who identify as American Indian or Alaska Native (AI/AN) and another race or ethnicity, but whose Indigenous identity is not recognized in state records. This occurs because current federal and state demographic data reporting practices require a student to identify as only one ethnic or racial group. As a result, schools lose out on federal funding that supports Native education.

For years, Indigenous education advocates have pushed for alternative data reporting practices, such as Maximum Representation, that allow students to claim all tribal affiliations and ethnic and racial identities in school demographic reporting.

“At its core, this is about equity,” says Susan Hou, an education researcher and Washington STEM Community Partner Fellow who is also researching Indigenous land movements in their native home of Taiwan.

“The goal of Maximum Representation is not just about getting the student count right – it’s about supporting student needs and academic goals through quality data.”

In partnership with the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction’s (OSPI) Office of Native Education (ONE), Hou conducted a series of conversations with Indigenous education leaders from across the state exploring how their communities are impacted by data reporting. Hou shared the learnings from these conversations in a recently published knowledge paper on Maximum Representation.

How a data process erases cultural identity

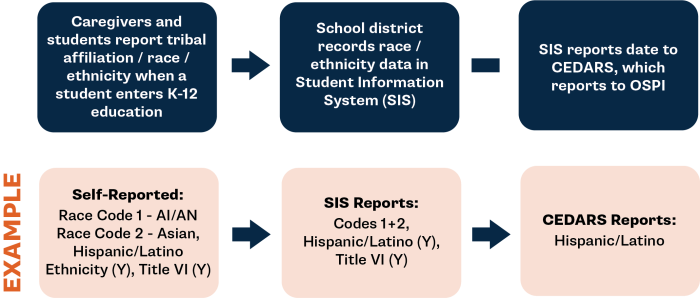

It starts with a form. When a student enrolls in school, they, or their guardians, fill out paperwork on the student’s demographic data. This is recorded at the district-level, where racial and tribal affiliation data are separated into component parts and sent to a state-level data warehouse where it is then prepared for federal reporting.

This is where the mechanics of the Native student undercount kick in: students who identify as more than one tribal affiliation, ethnicity, or race are recorded as only one ethnic or racial category on federal forms. The result is that more than 50,000 multiracial Native students are dropped from Washington’s Native student count (see graph above)—and their schools never receive the additional federal funding earmarked to support Native students.

“That question comes up every once in a while, ‘well, if you focus on this group, what happens to the rest of the groups?’ The answer is usually if you focus on the most marginalized students, everybody is going to have a better experience.”

-Dr. Kenneth Olden

The journey to data sovereignty

Maximum Representation differs from the current federal reporting methods in that it counts each component of a student’s Indigenous and racial identity towards demographic totals rather than student population totals. It is part of a push by Indigenous education advocates for greater involvement with how data is collected, compiled and shared with Indigenous communities. Such “data sovereignty” is a tribal nation’s right to control its data or opt out of federally and state-mandated data projects, and it goes beyond student enrollment.

School districts hold a wealth of student information that would be of interest to tribal governments – including awards, attendance, and disciplinary records; sports participation; and standardized test scores.

Nobody knows this better than Dr. Kenneth Olden, the Director of Assessment and Data at Wapato School District in Yakima County. In discussion with Hou, Dr. Olden recalls working with a school that seemingly had no record of disciplinary action towards Native students. He eventually found that the records existed – they just hadn’t been digitized. After digitizing the data and applying Maximum Representation, he got insights into Native absenteeism – an indicator of unfavorable graduation outcomes. He was also able to digitize records for Black students.

Dr. Olden says: “That question comes up every once in a while, ‘well, if you focus on this group, what happens to the rest of the groups?’ The answer is usually if you focus on the most marginalized students, everybody is going to have a better experience.”

Where we came from, we’re going

The Native student undercount is part of a longer history of colonialism in the U.S. education system– from boarding schools, to social workers’ abduction of Native children, to government efforts to relocate Native Americans to urban cities and erase reservations in the 1950s. This history is entwined with one of Native advocacy and resistance, which led to the creation of federal funding for Native education in the 1960s.

It’s all contributed to the current moment, in which over 90% of Native students receive attend public schools and yet many Native families are reticent to disclose their child’s indigenous identity.

Jenny Serpa, a college lecturer who teaches on Federal Indian law and tribal governance told Hou that some tribal families have shared that when their student(s) identify as Native, they are often asked to complete more forms and end up receiving more school communications. Serpa said, “While these are likely intended to engage students and families, some parents have reported that they just become overwhelming.”

She added: “Identifying as tribal also leads to students experiencing microaggressions or being asked to represent the tribal voice in the school. These poor experiences have led to parents opting to withhold their students’ identity, so they aren’t treated in a bad way.”

Next Steps: Improving tribal consultation

Enriching Native education isn’t possible without listening to tribal nations and communities. ONE’s Dr. Mona Halcomb shared with Hou that recent legislation sets up guidelines for a consultation process between tribal nations and school districts on issues impacting Native students, including accurate identification of Native students and sharing district-level data with federally recognized tribes.

The Maximum Representation knowledge paper provides more details about the tribal consultation process as well as resources for education administrators at the district and state levels. These include: improving data reporting, handling disaggregated data, and creating policies to implement Maximum Representation.

With many state stakeholders joining indigenous education leaders in advocacy for Maximum Representation, Hou is hopeful: “I’m excited to see how this will bring forth collaborations, policies, and coalitions that prioritize culturally sustaining Native education and Native student wellbeing.”