Principal Turnover

The uneven effects of principal turnover

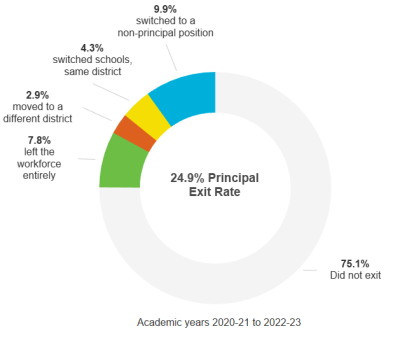

At the end of the 2022-23 school year, 1 in 4 Washington K-12 school principals left their job, affecting under-resourced schools in both urban and rural settings.

A policy brief published by researchers at the University of Washington College of Education found that in 2023, principal turnover reached 24.9%—up from 20% pre-pandemic levels. Lead researcher, associate professor David Knight, said although principals left their posts across many different contexts—urban, rural and suburban—not all departures represented fewer educators in the system. Data on principal turnover from 2022 show that 9.9% left principal positions for other jobs in the K-12 system while 7.8% left the K-12 workforce entirely.

“Principal turnover disproportionately impacts schools in high-poverty areas, and schools with a high proportion of BIPOC students. Knowing this can help create targeted solutions.”

-David Knight, Associate Professor, UW College of Education

When the researchers controlled for school environment (that is, size of student body, and geographic setting), there were not significant differences in turnover among principals based on their race and gender, but principal turnover still differed across school contexts, including student demographics. Knight said, “Principal turnover disproportionately impacts schools in high-poverty areas, and schools with a high proportion of BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, People of Color] students. Knowing this can help create targeted solutions.”

UW Examined records from 1998—present

Knight and his colleagues, who have been researching educator turnover as part of a three-year grant from the National Science Foundation, researched links between principal turnover, school characteristics and personnel demographics. They reviewed OSPI’s personnel files from 1998-2023, linking 7,325 principals records with student enrollment data from 295 districts as well as Tribal Compact Schools and charter schools. They also looked at variables such as principals’ total years of experience, race/ethnicity and gender, school grade level and school demographics, and district locale and size.

They found that over the past 26 years, principal turnover in Washington state remained generally consistent, at 20%, before spiking to 24.9% in 2023. However, a dig into disaggregated data revealed consistently greater principal turnover among novice and late career principals, so the experience profile of the principal workforce in a given year is associated with the amount of principal turnover that year.

Early and late career departures

The research shows that between 1998-2010 a larger share of principal turnover was likely driven by retirement. After 2010, a larger proportion of the principal workforce were mid-career, with 10-15 years of experience. And today, while the data shows a slightly younger principal workforce than in years past, many are at or nearing retirement age (see Figure 3).

Knight noted that novice principals’ departures may reflect a lack of support in under-resourced schools. He and his team looked at the characteristics of the schools principals left: the school size, grade levels, demographics and level of poverty among the student body. These factors all influence what resources are available, and indirectly, have significant effects on job satisfaction and turnover rates.

According to the UW analysis, principal turnover rates were highest—30%—in schools where there is a high percentage of low-income students, and students of color, as well as those serving more English Language Learners and students attending special education.

Knight said being in an under-resourced school means that principals face even greater pressure because they may lack assistant principals, counselors, or mental health specialists. During the pandemic, some 1,400 children in Washington lost a caregiver to COVID-19. This, coupled with findings from the 2021 U.S. Teacher Survey that point to widespread job-related stress and depression as key drivers of teacher turnover, give a sense of the difficult school environments principals oversee.

Knight added that, “Principals have also faced new challenges associated with transitions between online and in-person learning, and mediating curriculum disagreements pertaining to U.S. racial history and LGBTQ+ populations.” Also, the number of educators applying for principalships in Washington is likely impacted by the state’s favorable conditions for teachers, who secured a significant pay rise in 2019. This may have reduced the pay incentive for teachers who might have sought higher pay in a principalship.

Disproportionate impacts

According to the UW analysis, principal turnover rates were highest—30%— in schools where there is a high percentage of low-income students, and students of color, as well as those serving more English Language Learners (ELL) and students attending special education. This impacts several large urban districts, as well as smaller more rural districts in the state.

The research shows that principal race/ethnicity and years of experience are factors in principal turnover rates, but that overall schooling contexts play a greater role, with turnover was correlated with student demographics along economic and racial lines. Put another way, low-income students attend schools with a principal turnover rate that is 6.1 percentage points greater than non-low-income students.

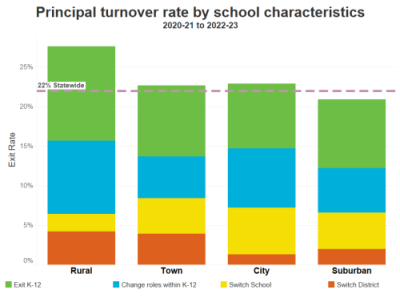

Knight said “This graphic tells us that for students living in poverty, and students who identify as BIPOC, their learning environments are more like to be disruption by leaderships turnover. At rural schools, the turnover rate reached 27.5% during the pandemic, an unsustainably high number.”

Longer-term Impacts

Erin Lucich, the Director of School Improvement & Educational Leadership in southwest Washington’s ESD 112, said funding, especially in rural districts, is often to blame. “We have higher turnover in principal and superintendent positions, especially when they are moving from outside the area for the experience.”

Lucich said that over her career she’s seen the impacts of high principal turnover, which often result in school staff being shy to adopt new initiatives because they might expect these initiatives to be deprioritized when the principal leaves. Lucich said, for a principal to have a lasting effect on a school culture, they have to stay at least five to seven years.

She said, “I recall a principal who came in with the intent to dismantle existing structures that no longer serve all students. This was a heavy lift to get everybody on board—in the school as well as the community. But once that principal left after their third year, the work stalled, and things have more or less gone back to how they were.”

Solutions within our grasp

The researchers believe solutions are within our grasp. Knight said, “A hundred different reasons brought this issue to the fore during the pandemic. But it’s important to remember this is not a statewide crisis. Turnover is highest in schools with high poverty populations, in rural areas as well as in urban centers and in school that serve greater percentages of BIPOC students. The policy solutions need to be targeted, and can’t be a one-size-fits-all.”

The research team emphasized community-based solution, and deeper analyses to identify root causes, but offered the following policy recommendations:

- Track principal turnover data: there is substantial variation in principal turnover both over time for specific school districts, and across districts in any given year. Having access to OSPI’s S-275 database will help schools explore and address these variations.

- Address the root cause of acute and long-term school leadership instability. Recent teacher pay increases diminishes any monetary incentive to move into the leadership roles, along with the daily management of burnout and stress, secondary trauma, and greater political pressure related to school closures, masking and disease prevention. The state should invest in supporting the 500 new principals in order to retain them.

- Target state resources to districts with high principal turnover. Reforming the finance system to allocate funding progressively, with a greater amount of per-pupil state and local revenues going to higher-poverty school districts, would directly benefit districts with the highest principal turnover rates.

- Consider accountability provisions related to principal turnover. Efforts to increase accountability around principal turnover should start with examination of what role state education agencies can play in providing supports. Include leader retention in the Washington School Improvement Framework.

Note: The research referenced in this post is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 2055062. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of funders.

***

This STEM Teaching Workforce blog post was written in partnership with researchers from the University of Washington’s College of Education, based primarily on their research into the COVID-19 pandemic’s impacts on the educational workforce.