Integrating science in elementary classroom pays dividends later

From nature walks to “observing phenomena”

Do you remember the first time you picked up a leaf? You were probably two or three years old and exploring the outdoors. Perhaps you noticed its unique shape, and if it was crackly-dry or wet. Maybe an adult helped you make a crayon rubbing of its veins and you learned those are how leaves get nutrients—just like people.

Congratulations—you did science!

“Observing phenomena” is how most of us were introduced to science learning, followed by asking questions, making investigations or testing ideas, and learning to explain one’s thinking. But in elementary classrooms across the state students only receive, on average, 1.5 hours of science education, out of 30 classroom hours each week. The result is that students are not prepared for science in the higher grades.

Tana Peterman is the program officer for k-12 education at Washington STEM, which leads the Leadership and Assistance for Science Education Reform (LASER)* Alliance. LASER and OSPI both host online webinars to help elementary teachers and school leaders make the case for greater science content in k-5 classrooms. LASER also offers free online resources and strategies to integrate science into already packed classroom schedules.

Their recent webinar, “Elementary science needs a comeback”, aimed to do just that: by highlighting examples from school districts around the state where elementary teachers excel at integrating science concepts into math and reading lessons.

Tana Peterman said, “With elementary science we keep putting band aids on a system that needs open heart surgery. We talk about educating the whole child, yet we keep asking them to learn in silos.”

Early science foundation

At its core, science is observing and making sense of the world around us—something children are well equipped to do thanks to their innate curiosity.

Michelle Grove is science coordinator for Educational Service District (ESD) 101 in Spokane and has 25 years of teaching experience, including biology, chemistry, and anatomy. She is also LASER director for the Northeast region and statewide co-director.

“Learning science in elementary grades is the underpinning of everything that comes after. Without it, kids lose interest and then don’t engage deeply. Even if they are provided with high-quality science experiences in the middle and high school levels, without those foundational skills, like the importance of evidence-based reasoning, they’ll struggle to exit our k-12 system as scientifically literate adults.” She emphasizes that this means understanding that science isn’t just working in a lab, but also planning and carrying out investigations, solving problems, creating models, analyzing and interpreting data, constructing explanations, and designing solutions.

“By the time kids are in high school, in terms of science education, there are the ‘haves’ and the ‘have-nots. Kids who don’t have science in elementary or middle school may fall behind or avoid science classes, thinking, ‘I’m not good in science.’”

– Lorianne Donovan-Hermann, Science Coordinator at ESD 123

Lorianne Donovan-Hermann, science coordinator for ESD 123 in Southeast Washington and Southeast LASER Alliance Director, said, “By the time kids are in high school, in terms of science education, there are the ‘haves’ and the ‘have-nots’. Kids who don’t have science in elementary or middle school may fall behind or avoid science classes, thinking, ‘I’m not good in science.’ And they’ll never consider taking an AP level course. They’ll end up on a completely divergent course.”

While it’s true not every child wants to be a scientist when they grow up, every student does need basic scientific knowledge to navigate their health and environment, understand their choices at the ballot box, and even their maintain their homes. Donovan-Hermann said, “Basic homeownership requires layers of scientific knowledge to safeguard from toxic mold from a leaky pipe or understanding the dangers of a gas leak. And in our own bodies, knowing how viruses work—and following the latest scientific studies of how to treat it—can help us keep our families safe.”

Overcoming the time-crunch

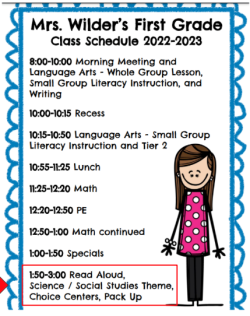

Even before the pandemic resulted in lower test scores for students across the country, elementary teachers struggled to fit science education into an already-packed schedule. The upstream reason for this is that most elementary classrooms focus on math and reading, and science isn’t assessed until fifth grade in Washington. Also, since most elementary school teachers aren’t also endorsed in science, for some, it can feel out of reach to teach it. However, there is a promising approach: integrate scientific concepts into reading, writing and math lessons.

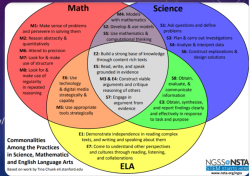

Michelle Grove said there is a misconception that math and reading are taught in isolation. “In reality, scientific themes can be integrated into math or reading/writing assignments—this is called phenomena-based writing.”

Grove said she has worked with teachers who used plant anatomy lessons for phenomena-based reading and writing from Open Education Resources (OER), a free resource for teachers. “Students’ understanding went from creating simple drawings at the beginning of the year, to showing these gapless explanations about scientific processes.”

Another example of science integration is from first and fifth grade teachers in the Olympia area who planned for fifth graders to visit the younger class to share their science learnings. Years later, fifth grade science teacher, TJ Thornton, recalled how impactful this was for one student in particular:

“One of the boys in my class asked, ‘When are we going to do that thing with the first graders’? Now, he wasn’t necessarily the strongest student academically, and even though it was over half his lifetime ago, he’d been thinking about it and was excited to share science with the first graders.”

Evolution of science: from “absolutes” to integrating new discoveries

For many, the Covid-19 pandemic has brought home the importance of understanding basic scientific processes. Donovan-Hermann, science coordinator in Pasco, said technological advances have had a major impact on scientific understanding.

“Science has changed so much since I was in high school. Before, we learned about ‘the absolutes’, but now, being able to change our minds when the science changes—that is crucial.”

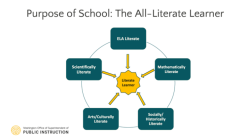

Also, understanding evidence-based reasoning—whether in science or political science—is crucial to graduating students who are All-Literate Learners.

“Science has changed so much since I was in high school. Before, we learned about ‘the absolutes’, but now, being able to change our minds when the science changes—that is crucial.”

– Lorianne Donovan-Hermann, Science Coordinator at ESD 123

Michelle Grove recalled: “My seventh-grade daughter’s class focused on the importance of evidentiary-based thinking as a year-long theme. So, when she observed political commentators on TV arguing without evidence, she was upset, saying. ‘They shouldn’t be allowed to do that!’”

Ask for more science

Grove said one way parents can support science education is by attending their school’s open house and asking, “What are you doing with Reading, Math and Science?” She said what helps elementary science to thrive is a nexus of 1) administrators who champion science; 2) teachers who have skills and confidence, and 3) funding from a system that prioritizes it.

Having support from the local school board can help prioritize science integration in the classroom. Scott Killough is the regional science coordinator for ESD 113 and a member of the Tumwater District School Board. He recalled a conversation the school board had with its former superintendent toward the end of the Covid-19 pandemic. The board determined that to have long-lasting change Social Emotional Learning (SEL) should be included in the annual budget. “It is now a line item in our budget, regardless of changes to personnel. SEL is here to stay.” He said a similar approach could help with integrating Elementary Science.

Similarly, Kimberly Astle from the Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) encouraged teachers during the February webinar to think of how science can be an anchor to support English Language Arts learning. “I see forward motion by seeing how science is part of a system of learning.”

Science’s WEIRD problem

Integrating science into elementary classrooms can also have a positive impact on advancing racial equity —if lessons encourage students to bring their cultural learnings and values into science investigations. In recent decades, educators and activists have drawn attention to science education’s “WEIRD” problem, that is, it was centered on science from Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) societies. Science in this context often ignored contributions by women and people of color, or even claimed or wrongly attributed their discoveries to white male colleagues. This can leave students with the idea that only certain kind of people “do science”.

When Donovan-Hermann taught 3rd grade in the Tri-Cities area, she attended a week-long, teacher-scientist partnership (TSP) with a geologist at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratories. The goal was to increase teacher knowledge and bring what she learned back to her students.

Grove said one way parents can support science education is by attending their school’s open house and asking, “What are you doing with Reading, Math and Science?”

“I brought back photos of me working in the field with the scientist to show my class. One little girl, from a rural community, looked at the photo on my phone and then back at me and said, ‘Oh—that’s the wrong picture. Where’s the photo of the scientist?’ I looked down and said, ‘That’s her—that’s Dr. Frannie Smith.’ This little girl didn’t know women could be scientists.”

That inspired Donovan-Hermann to invite the scientist, “Dr. Frannie” to speak to her class. Thus began a partnership that she believes influenced many of her students. “Years later, I ran into the little girl; she was now about 20 years old and working to save up for college. I remember her excitement as she talked about meeting Dr. Frannie.”

The STEM Teaching Tools blog offers guidance on discussing race in the context of science education, “Race and racism are present in science classrooms. Students, no matter how young, are aware of race, and mirror societal biases. They notice who is in the room — both literally (you and other students) and figuratively (who does science? what does a scientist look like?).”

Washington STEM is advocating for science integration in elementary classrooms so all students in Washington can answer the question, “Who does science?” with one word:

“Me.”

*organized by Leadership and Assistance for Science Education Reform (LASER) is a statewide organization, led by Washington STEM in partnership with OSPI, Education Service Districts (ESD) and the Institute for Systems Biology. (Learn more about how LASER came about.) Together, they provide webinars, online resources focused on raising equity in k-12 science education.